Von Willebrand Disease (VWD)

What is von Willebrand Disease?

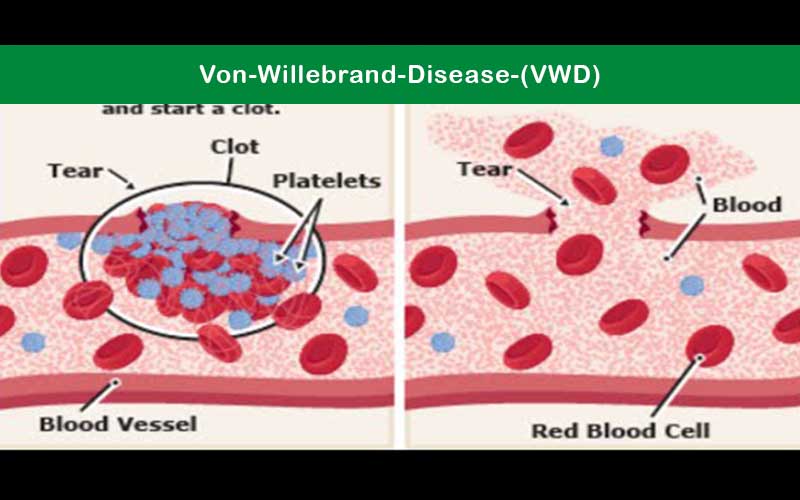

Von Willebrand disease (VWD) is a blood disorder in which the blood does not clot properly. Blood contains many proteins that help the body stop bleeding. One of these proteins is called von Willebrand factor (VWF). People with VWD either have a low level of VWF in their blood or the VWF protein doesn’t work the way it should.

Normally, when a person is injured and starts to bleed, the VWF in the blood attaches to small blood cells called platelets. This helps the platelets stick together, like glue, to form a clot at the site of injury and stop the bleeding. When a person has VWD, because the VWF doesn’t work the way it should, the clot might take longer to form or not form the way it should, and bleeding might take longer to stop. This can lead to heavy, hard-to-stop bleeding. Although rare, the bleeding can be severe enough to damage joints or internal organs, or even be life-threatening.

Who is Affected

VWD is the most common bleeding disorder, found in up to 1% of the U.S. population. This means that 3.2 million (or about 1 in every 100) people in the United States have the disease. Although VWD occurs among men and women equally, women are more likely to notice the symptoms because of heavy or abnormal bleeding during their menstrual periods and after childbirth.

Types of VWD

Type 1

This is the most common and mildest form of VWD, in which a person has lower than normal levels of VWF. A person with Type 1 VWD also might have low levels of factor VIII, another type of blood-clotting protein. This should not be confused with hemophilia, in which there are low levels or a complete lack of factor VIII but normal levels of VWF. About 85% of people treated for VWD have Type 1.

Type 2

With this type of VWD, although the body makes normal amounts of the VWF, the factor does not work the way it should. Type 2 is further broken down into four subtypes?2A, 2B, 2M, and 2N?depending on the specific problem with the person’s VWF. Because the treatment is different for each type, it is important that a person know which subtype he or she has.

Type 3

This is the most severe form of VWD, in which a person has very little or no VWF and low levels of factor VIII. This is the rarest type of VWD. Only 3% of people with VWD have Type 3.

Causes

Most people who have VWD are born with it. It almost always is inherited, or passed down, from a parent to a child. VWD can be passed down from either the mother or the father, or both, to the child.

While rare, it is possible for a person to get VWD without a family history of the disease. This happens when a “spontaneous mutation” occurs. That means there has been a change in the person’s gene. Whether the child received the affected gene from a parent or as a result of a mutation, once the child has it, the child can later pass it along to his or her children. Rarely, a person who is not born with VWD can acquire it or have it first occur later in life. This can happen when a person’s own immune system destroys his or her VWF, often as a result of use of a medication or as a result of another disease. If VWD is acquired, meaning it was not inherited from a parent, it cannot be passed along to any children.

Learn more about how VWD is inherited »

Signs and Symptoms

The major signs of VWD are:

Frequent or Hard-to-Stop Nosebleeds

People with VWD might have nosebleeds that:

- Start without injury (spontaneous)

- Occur often, usually five times or more in a year

- Last more than 10 minutes

- Need packing or cautery to stop the bleeding

Easy Bruising

People with VWD might experience easy bruising that:

- Occurs with very little or no trauma or injury

- Occurs often (one to four times per month)

- Is larger than the size of a quarter

- Is not flat and has a raised lump

Heavy Menstrual Bleeding

Women with VWD might have heavy menstrual periods during which:

- Clots larger than the size of a quarter are passed

- More than one pad is soaked through every 2 hours

- A diagnosis of anemia (not having enough red blood cells) is made as a result of bleeding from heavy periods

Longer than Normal Bleeding After Injury, Surgery, Childbirth, or Dental Work

People with VWD might have longer than normal bleeding after injury, surgery, or childbirth, for example:

- After a cut to the skin, the bleeding lasts more than 5 minutes

- Heavy or longer bleeding occurs after surgery. Bleeding sometimes stops, but starts up again hours or days later.

- Heavy bleeding occurs during or after childbirth

People with VWD might have longer than normal bleeding during or after dental work, for example:

- Heavy bleeding occurs during or after dental surgery

- The surgery site oozes blood longer than 3 hours after the surgery

- The surgery site needs packing or cautery to stop the bleeding

The amount of bleeding depends on the type and severity of VWD. Other common bleeding events include:

- Blood in the stool (feces) from bleeding into the stomach or intestines

- Blood in the urine from bleeding into the kidneys or bladder

- Bleeding into joints or internal organs in severe cases (Type 3)

Diagnosis

To find out if a person has VWD, the doctor will ask questions about personal and family histories of bleeding. The doctor also will check for unusual bruising or other signs of recent bleeding and order some blood tests that will measure how the blood clots. The tests will provide information about the amount of clotting proteins present in the blood and if the clotting proteins are working properly. Because certain medications can cause bleeding, even among people without a bleeding disorder, the doctor will ask about recent or routine medications taken that could cause bleeding or make bleeding symptoms worse.

Learn about tests to diagnose VWD »

Treatments

The type of treatment prescribed for VWD depends on the type and severity of the disease. For minor bleeds, treatment might not be needed.

The most commonly used types of treatment are:

Desmopressin Acetate Injection

This medicine (DDAVP®) is injected into a vein to treat people with milder forms of VWD (mainly type 1). It works by making the body release more VWF into the blood. It helps increase the level of factor VIII in the blood as well.

Desmopressin Acetate Nasal Spray

This high-strength nasal spray (Stimate®) is used to treat people with milder forms of VWD. It works by making the body release more VWF into the blood.

Factor Replacement Therapy

Recombinant VWF (such as Vonvendi®) and medicines rich in VWF and factor VIII (for example, Humate P®, Wilate®, Alphanate®, or Koate DVI®) are used to treat people with more severe forms of VWD or people with milder forms of VWD who do not respond well to the nasal spray. These medicines are injected into a vein in the arm to replace the missing factor in the blood.

Antifibrinolytic Drugs

These drugs (for example, Amicar®, Lysteda®) are either injected or taken orally to help slow or prevent the breakdown of blood clots.

Birth Control Pills

Birth control pills can increase the levels of VWF and factor VIII in the blood and reduce menstrual blood loss. A doctor can prescribe these pills for women who have heavy menstrual bleeding